Posted: May 27, 2007

Keith Feinstein's Videotopia Traveling Exhibit

Videotopia A Blast from the Past

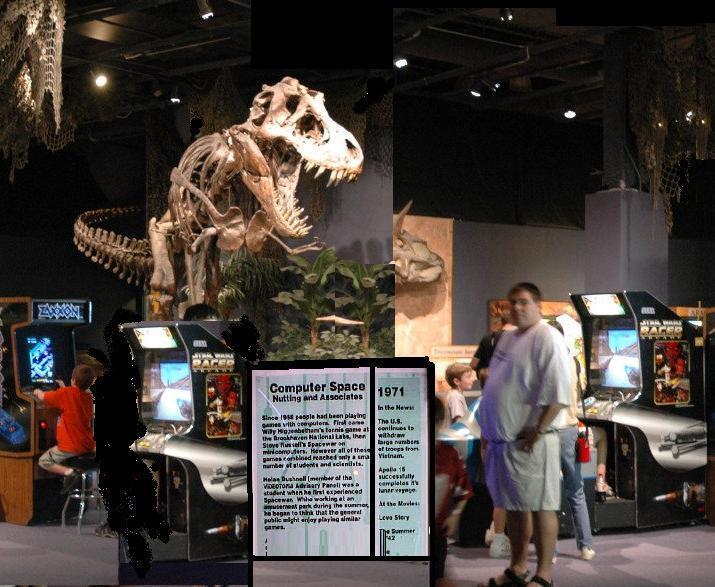

VIDEOTOPIA explores humanity's first giant leap into interactive electronic media The videogame.

Keith Feinstein's Videotopia Traveling Exhibit

Videotopia A Blast from the Past

VIDEOTOPIA explores humanity's first giant leap into interactive electronic media The videogame.

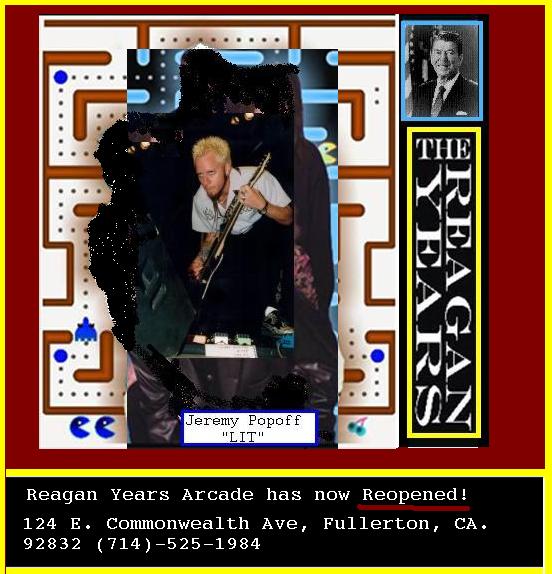

"Reagan Years" the 1980's Classics Arcade in Fullerton, CA

Has now Re-Opened and has a whole new facelift! (June 16, 2006)

"Reagan Years" the 1980's Classics Arcade in Fullerton, CA

Has now Re-Opened and has a whole new facelift! (June 16, 2006)

Reagan Years

This classic era arcade, "Reagan Years" is combined in a way with the ultra hip,

"The Sidebar Rock and Roll Cafe" is connected to Reagan Years and is co-owned by

the famous rock band guitarist from "Lit", Jeremy Popoff and businessman,

Sean Francis. Link

The Reagan Years is mostly a New Games Arcade with six classics in the back.

Jeremy, co-owner of the Slidebar/Reagan Years, has been slimming down the number

of classic games by at least 50% because the profits were not there, and there

are now newer games in the place of most of the classics.

The current games at Slidebar are as follows: 720 degrees, Asteroids, Defender,

Frogger, Gauntlet, Ms Pac-man/Galaga: Class of '81, Rampage, Track & Field, Tron,

and Centipede (which was not functioning), 2 felty pool tables, 1 air hockey, and

the biggest big buck hunter.

Thank you!

Paul Dean, Spy Hunter Champion, June 28, 1985

The Fender Museum

On July 13th, 2002 the Fender Museum of Music and the Arts carved a place for itself

in music history with the official opening of its brand new 33,000 square foot building

in Corona, CA Link

Fender

Reagan Years

This classic era arcade, "Reagan Years" is combined in a way with the ultra hip,

"The Sidebar Rock and Roll Cafe" is connected to Reagan Years and is co-owned by

the famous rock band guitarist from "Lit", Jeremy Popoff and businessman,

Sean Francis. Link

The Reagan Years is mostly a New Games Arcade with six classics in the back.

Jeremy, co-owner of the Slidebar/Reagan Years, has been slimming down the number

of classic games by at least 50% because the profits were not there, and there

are now newer games in the place of most of the classics.

The current games at Slidebar are as follows: 720 degrees, Asteroids, Defender,

Frogger, Gauntlet, Ms Pac-man/Galaga: Class of '81, Rampage, Track & Field, Tron,

and Centipede (which was not functioning), 2 felty pool tables, 1 air hockey, and

the biggest big buck hunter.

Thank you!

Paul Dean, Spy Hunter Champion, June 28, 1985

The Fender Museum

On July 13th, 2002 the Fender Museum of Music and the Arts carved a place for itself

in music history with the official opening of its brand new 33,000 square foot building

in Corona, CA Link

Fender

The Fender Museum

365 North Main Street

Corona, CA 92880

951.735.2440

The Fender Museum

365 North Main Street

Corona, CA 92880

951.735.2440